On May 9, shortly after her 12th birthday, Muna left her home in Khartoum and walked to the local shop. She often ran errands on her own and would quickly return to her mother. But not this time. Two soldiers buying cigarettes noticed Muna as she was choosing bread – one grabbed her arm while the other raised his rifle, threatening the store owner to keep his distance. They dragged her to a construction site nearby and raped her.

The soldiers were members of the Rapid Support Forces, a paramilitary group that’s been fighting the Sudanese Army for control of the capital city for the past three months. Both have a fearsome reputation. Dumped on the side of the road, bleeding and in pain, Muna made it home with the help of the shopkeeper, a family friend. Her parents filed a complaint with judicial authorities, who referred them to a psychologist, who in turn, advised them to avoid the nearest hospital because it was controlled by the RSF. Instead, they checked Muna for sexually-transmitted infections at a private clinic and asked a pharmacy for sanitary pads and painkillers.

Days later, the family fled the city. Before dropping off the radar, Muna’s parents gave permission for her story to be shared. Bloomberg News is not disclosing their identities for safety reasons, and is using Muna as an alias. Her rape — revealed in government documents reviewed by Bloomberg and verified by two aid workers — is part of a much wider pattern of soldiers committing sexual violence in Sudan’s conflict. Many cases are going unreported, activists say, in a country where foreign journalists are essentially banned by the government.

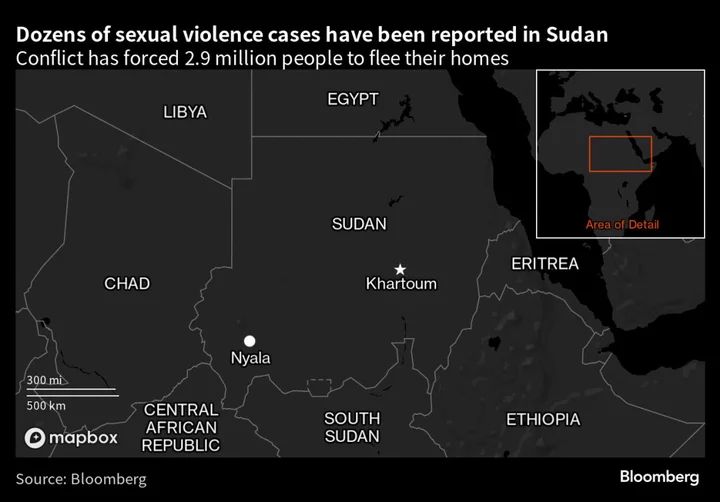

Fighting erupted in April when the two generals who’d been ruling Sudan since an October coup began arguing over an internationally backed plan to transition to democracy. As clashes rumble on out of the media spotlight, neighbors — Chad, the Central African Republic, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Libya and South Sudan — as well as the US and Saudi Arabia are trying to broker peace to avoid a full-blown civil war that spills across borders.

More than 2.9 million people have left their homes since the conflict began, with almost 700,000 of them seeking refuge in the region. Around 3,000 others have been killed, according to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, a US-based research group. Both the RSF and the Sudanese Army are accused of abuses, including sexual violence against women and girls like Muna.

The UN Human Rights Office in Sudan said it has received credible reports of 21 incidents of conflict-related sexual violence against at least 57 women and girls. Sulima Ishaq, director of the government’s Unit for Combating Violence against Women under the Ministry of Social Development, says her team has recorded 88 incidents — 42 in Khartoum and the rest in the Darfur region, a scene of ethnically-motivated attacks.

Those cases account for only a tiny fraction of the total, according to Ishaq, who documented Muna’s assault. “The numbers do not represent what is really happening,” she said. In the largely conservative country where most positions of power are held by men “there is a lot of stigma around sexual violence, and it all goes under-reported.”

Health workers and activists say the vast majority of girls and women coming forward with allegations of abuse point the finger at the RSF. A spokesperson for the paramilitary group denied what it called unfounded allegations, adding “the RSF vehemently condemns all forms of unethical conduct and categorically rejects the accusations leveled against our forces.” A spokesperson for the Sudanese army did not respond to questions.

One of the worst documented cases so far in the conflict took place on May 1 when RSF soldiers abducted 25 women — aged between 14 and 56 — traveling from Nyala, in the Darfur region, to a camp for the internally displaced. They were taken to a hotel where they were repeatedly raped, according to an incident report written by Ishaq’s unit and seen by Bloomberg. Seven refused medical help, either because they feared being stigmatized or because of the trauma they endured, according to Ishaq.

Rape and sexual assault during war are aimed at humiliating a community as well as the individual into total submission, and both are considered war crimes and a breach of international humanitarian law.

In Sudan, such acts are also being committed by fighters to try to pressure civilians to leave their homes, which they take over and use as safehouses or to position snipers, according to Enas Muzamil, a women’s rights activist who works with victims of sexual assault across Sudan. “Militia members commit these crimes in Khartoum and Darfur, in addition to looting, occupying homes and expelling their residents,” she said.

Read More: What’s Behind the Fighting in Sudan and What It Means

In normal times, doctors and health workers would help victims of sexual violence, but their numbers are dwindling. At least 27 have been killed by gunfire or shelling since fighting began, according to the Preliminary Committee of Sudanese Doctors, an association documenting deceased medical staff. At least three doctors have been abducted during the same period, either for their links to pro-democracy resistance groups or to care for injured combatants, according to Abdul Mounem, a senior member of Sudan’s Central Committee of Sudanese Doctors. Since most medical supplies are distributed to civilians through the Ministry of Health, the RSF is also looting and commandeering hospitals, he said.

That leaves few options. Countless women and girls are turning to social media, according to Mahasin Dahab, head of the Sudanese Archive group that uses open source intelligence to document human rights violations. She said online activists have referred some sexual assault cases to NGOs on the ground.

Sexual assault by both the RSF and the army is the result of historic impunity, according to Dahab. “The laws don’t support our claims of gender-based violence,” she said, adding that before war the police violated women’s bodies but now, “the RSF uses gender-based violence as a weapon of war.”