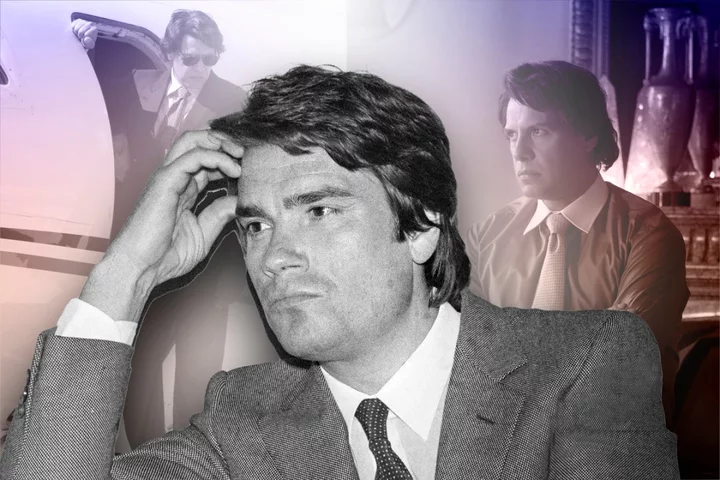

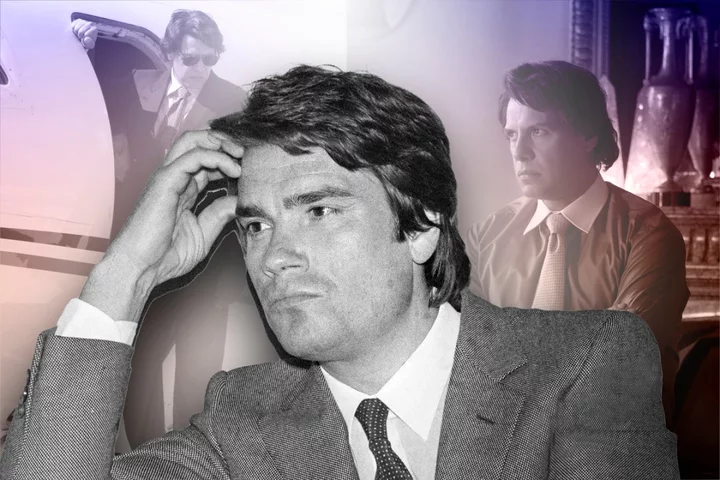

‘Very rich, very famous, and very powerful’: How Bernard Tapie became France’s first tycoon – and wound up in prison

If you’ve grown up in France, Bernard Tapie is one of those people you’ve always been aware of, without being able to remember when you first heard about them, or what they’re currently famous for. In Tapie’s case, the answer varied throughout the years: at times, he was famous for his career as a businessman; at others, for his career in the world of sports. There was also politics, show business, and legal scandals, depending on when you asked. Only one constant remained: from his rise to fame in the 1980s to his death in 2021, Tapie was notorious. A new Netflix series dramatizes 30 years of his life, charting his humble beginnings, his not-so-humble early successes, and the biggest legal controversy of his life—for fixing a soccer game in favour of Olympique de Marseille, Marseille’s soccer team, which he then owned. In France, the show is simply called Tapie—a name known to virtually anyone. In the US, it’s titled Class Act, an apparent wordplay to nod both to Tapie’s exceptional destiny and to his status as what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called a “transfuge de classe”—someone who moves from one social milieu to another. The show, comprising seven episodes, is a fascinating examination not just of the man himself, but of the country that allowed his ascent. It casts an eye back on the lionized men of the 1980s and asks: at what cost did we create them? And what are we meant to do with them now? “In the same way that there was Trump in the US, Berlusconi in Italy, there was Tapie in France,” Tristan Séguéla, who directed and co-wrote the series, tells The Independent in a video call. “The 1980s had a strong mythology around these characters who could embody everything, and who were very rich, very famous, and very powerful all at once.” Bernard Tapie was born in 1943 in Paris. His father was a laborer, his mother a nurse’s aide. He first sought fame as a performer, then in business. In the 1960s, he won a televised singing contest under the name Bernard Tapy—a much more American-seeming spelling of his last name. But that success was short-lived, and Tapie soon transitioned to selling televisions for a living. In the late 1970s and through the 1980s, he became known for purchasing companies on the verge of bankruptcy and reselling them for considerable profit. In the 1990s, he entered politics, as a member of President François Mitterrand’s government and as a Congressman. That same decade, he bought and sold the athletic apparel brand Adidas. The 1990s also saw Tapie’s biggest legal controversy: in 1995, Tapie was sentenced to eight months in prison for bribing members of the opposite team to ensure Marseille’s victory in a final match against Valenciennes. (Tapie had become the president of the Marseille team in 1986.) All of those events are depicted in Tapie. In real life, the story goes on, with more legal troubles (Tapie was sentenced to six months in prison for tax fraud in 1996) and more reinventions. To go through Tapie’s biography is to go through the story of a man who never retreated into anonymity and never stopped believing that the system would, in one way or another, bail him out. In the late 1990s and 2000s, he turned to acting and TV host gigs. In the 2010s, he became the owner of a media company. Tapie was diagnosed with stomach and esophagus cancer in 2017. He died of the disease in October 2021, aged 78. The actor Laurent Lafitte, who brilliantly portrays Tapie in the Netflix series and developed it with Séguéla, has spent time pondering Tapie’s story and what it represents. Tapie, he says in a phone call, was “a kid from the suburbs” raised in part by a Communist father. He views Tapie in that way in opposition to Trump, who long claimed to have received a “small” $1m loan from his father, “as if that were $10”, Lafitte says. Not only that, but that number is substantially false; Fred Trump’s financial support of his sum extended far beyond that sum. Tapie “did not have the same starting point as Trump at all”, Lafitte says, which, in his view, renders Tapie’s boundless ambition more palatable. But he is clear about Tapie’s “ultra liberalism”, and the way capitalism enabled his ascent: Tapie “bought failing companies and brought them back to financial health without concerning himself for the employees’ social wellbeing,” he says. Back in the 1980s, Tapie’s open ambition was considered “novel in France, where we have a rather discreet, reserved rapport with success, and especially with money.” In Tapie, Lafitte says, “we had someone who brandished material success as an absolute accomplishment.” The French language sometimes borrows words from English wholesale, not bothering to come up with a translation. “Fun”, for example, does not have a French equivalent. French people simply say “fun” with a French accent and carry on as usual. “Weekend” is another example. The words used to describe Tapie at various points in his career, Lafitte points out, do not have equivalents in French—there is no French word for “tycoon”, “self-made man”, or even “success story” (if one chooses to see Tapie that way). “These are English words that represent a kind of ultra liberal success that wouldn’t have been shocking for Americans, nor perhaps for some British people, back in the days,” Lafitte says. “But in France, it was really new.” Each episode of Tapie, the series, opens with a disclaimer that states the show is “inspired by real facts”, namely the big parts of Tapie’s life that were already known to the public. The show then takes liberties, imagining various scenes, giving viewers an interpretation of Tapie’s life rather than a date-by-date account. “Fiction worked [in the show] in the service of reality,” says screenwrite Olivier Demangel in a video call. He cites the German philosopher Theodor W Adorno, who, in reference to the works of Honoré de Balzac, wrote about “realism by way of losing reality.” “To me, that’s exactly it,” Demangel says. “[Adorno] was talking about Balzac, but we’ve always thought that Tapie had something of a Balzac character.” Not that the show is entirely disconnected from reality. To research the show, the team read around 40 books, Demangel says, and dug into television archives. “We really worked on the idea that Tapie was kind of the embodiment of television,” Demangel says. “Like a TV salesman who wanted to get inside the machine, and who sort of became television. We realized that he went through every television format, and that he had his downfall at the same time the world moved on to the internet. It’s as though the internet killed the world and Tapie.” Séguéla brought another real-world perspective: his father, Jacques Séguéla, was a prominent French publicist, and a friend of Tapie’s. The younger Séguéla has childhood memories of Tapie spending part of his vacations at the Séguélas’ house. “I remember someone who attracted attention,” he says. “And [Tapie] had one quality—I think it’s the same way with the friends of everyone’s parents: There are those who pay attention to kids, and those who don’t notice them. [Tapie] treated everyone equally, adults and children. I liked that, especially since he was already a media monster by the time he came by. I’d see him on TV, and then I’d see him make paella for everyone. And sometimes, we’d quarrel, too. He would argue with me about a bit of the Tour de France, or soccer teams. I liked that too.” Despite this personal connection, Tapie, before his death, had voiced his opposition to the series. More recently, his family voiced their objections, too. But that was never a problem for Séguéla, nor Lafitte, nor Demangel. They were determined to write the show, and they didn’t particularly want Tapie or his relatives to contribute to the writing. Years ago, Séguéla made it clear to Tapie that he wasn’t seeking his permission to go ahead, Tapie “left him alone” and let him work in peace, Séguéla says. “It would have annoyed me if he’d felt hurt by the show, if he’d found it insulting or defamatory,” Lafitte says. “But I was comforted by the fact that our work was mainly impartial.” Despite the differences between Trump and Tapie, the team too had Trump on the mind while crafting the show. “I would even say that Tapie must have had Trump on his mind during his own rise to fame,” Séguéla says. Tapie, Séguéla points out, published a nonfiction book called Gagner (“to win”), a cross between a memoir and a book of business tips. Tapie’s book came out in 1986. Trump’s own book, The Art of the Deal, came out in 1987—three years after Trump appeared on the cover of GQ. The 1984 cover story was titled: “Success: How Sweet It Is. Men Who Take Risks and Make Millions.” Now, Lafitte struggles to imagine France’s other wealthy men, such as businessmen François-Henri Pinault or Bernard Arnault sing on TV or host a show—both things Tapie did. Still, Tapie’s story as told in the Netflix series seems inseparable from France itself. In Tapie’s tale, Lafitte sees “all the contradictions” of the country’s attitudes to success. “In France, we always tend to be wary of people who succeed materially,” he says. “[Tapie’s story] is the story of a time when the line became a bit more blurry, between [the traditional French mindset] and a more American mindset. He understood that very quickly.” Read More Like Harry, they wrote brutally honest memoirs about their families. What happened next? From Harry Styles to Emma Roberts: How celebrity readers became the book influencers we didn’t know we needed Slim Aarons started out photographing war – but his greatest assignment was in the trenches of fashion Hurricane Nigel expected to ‘rapidly intensify’ by Tuesday - latest Trump says he doesn’t worry about jail risk as he refuses to rule out self-pardon Front door of home where Sharon Tate was murdered sells for $127k

If you’ve grown up in France, Bernard Tapie is one of those people you’ve always been aware of, without being able to remember when you first heard about them, or what they’re currently famous for. In Tapie’s case, the answer varied throughout the years: at times, he was famous for his career as a businessman; at others, for his career in the world of sports. There was also politics, show business, and legal scandals, depending on when you asked. Only one constant remained: from his rise to fame in the 1980s to his death in 2021, Tapie was notorious.

A new Netflix series dramatizes 30 years of his life, charting his humble beginnings, his not-so-humble early successes, and the biggest legal controversy of his life—for fixing a soccer game in favour of Olympique de Marseille, Marseille’s soccer team, which he then owned. In France, the show is simply called Tapie—a name known to virtually anyone. In the US, it’s titled Class Act, an apparent wordplay to nod both to Tapie’s exceptional destiny and to his status as what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called a “transfuge de classe”—someone who moves from one social milieu to another.

The show, comprising seven episodes, is a fascinating examination not just of the man himself, but of the country that allowed his ascent. It casts an eye back on the lionized men of the 1980s and asks: at what cost did we create them? And what are we meant to do with them now?

“In the same way that there was Trump in the US, Berlusconi in Italy, there was Tapie in France,” Tristan Séguéla, who directed and co-wrote the series, tells The Independent in a video call. “The 1980s had a strong mythology around these characters who could embody everything, and who were very rich, very famous, and very powerful all at once.”

Bernard Tapie was born in 1943 in Paris. His father was a laborer, his mother a nurse’s aide. He first sought fame as a performer, then in business. In the 1960s, he won a televised singing contest under the name Bernard Tapy—a much more American-seeming spelling of his last name. But that success was short-lived, and Tapie soon transitioned to selling televisions for a living. In the late 1970s and through the 1980s, he became known for purchasing companies on the verge of bankruptcy and reselling them for considerable profit. In the 1990s, he entered politics, as a member of President François Mitterrand’s government and as a Congressman. That same decade, he bought and sold the athletic apparel brand Adidas.

The 1990s also saw Tapie’s biggest legal controversy: in 1995, Tapie was sentenced to eight months in prison for bribing members of the opposite team to ensure Marseille’s victory in a final match against Valenciennes. (Tapie had become the president of the Marseille team in 1986.)

All of those events are depicted in Tapie. In real life, the story goes on, with more legal troubles (Tapie was sentenced to six months in prison for tax fraud in 1996) and more reinventions. To go through Tapie’s biography is to go through the story of a man who never retreated into anonymity and never stopped believing that the system would, in one way or another, bail him out. In the late 1990s and 2000s, he turned to acting and TV host gigs. In the 2010s, he became the owner of a media company. Tapie was diagnosed with stomach and esophagus cancer in 2017. He died of the disease in October 2021, aged 78.

The actor Laurent Lafitte, who brilliantly portrays Tapie in the Netflix series and developed it with Séguéla, has spent time pondering Tapie’s story and what it represents. Tapie, he says in a phone call, was “a kid from the suburbs” raised in part by a Communist father. He views Tapie in that way in opposition to Trump, who long claimed to have received a “small” $1m loan from his father, “as if that were $10”, Lafitte says. Not only that, but that number is substantially false; Fred Trump’s financial support of his sum extended far beyond that sum.

Tapie “did not have the same starting point as Trump at all”, Lafitte says, which, in his view, renders Tapie’s boundless ambition more palatable. But he is clear about Tapie’s “ultra liberalism”, and the way capitalism enabled his ascent: Tapie “bought failing companies and brought them back to financial health without concerning himself for the employees’ social wellbeing,” he says.

Back in the 1980s, Tapie’s open ambition was considered “novel in France, where we have a rather discreet, reserved rapport with success, and especially with money.” In Tapie, Lafitte says, “we had someone who brandished material success as an absolute accomplishment.”

The French language sometimes borrows words from English wholesale, not bothering to come up with a translation. “Fun”, for example, does not have a French equivalent. French people simply say “fun” with a French accent and carry on as usual. “Weekend” is another example. The words used to describe Tapie at various points in his career, Lafitte points out, do not have equivalents in French—there is no French word for “tycoon”, “self-made man”, or even “success story” (if one chooses to see Tapie that way).

“These are English words that represent a kind of ultra liberal success that wouldn’t have been shocking for Americans, nor perhaps for some British people, back in the days,” Lafitte says. “But in France, it was really new.”

Each episode of Tapie, the series, opens with a disclaimer that states the show is “inspired by real facts”, namely the big parts of Tapie’s life that were already known to the public. The show then takes liberties, imagining various scenes, giving viewers an interpretation of Tapie’s life rather than a date-by-date account.

“Fiction worked [in the show] in the service of reality,” says screenwrite Olivier Demangel in a video call. He cites the German philosopher Theodor W Adorno, who, in reference to the works of Honoré de Balzac, wrote about “realism by way of losing reality.” “To me, that’s exactly it,” Demangel says. “[Adorno] was talking about Balzac, but we’ve always thought that Tapie had something of a Balzac character.”

Not that the show is entirely disconnected from reality. To research the show, the team read around 40 books, Demangel says, and dug into television archives. “We really worked on the idea that Tapie was kind of the embodiment of television,” Demangel says. “Like a TV salesman who wanted to get inside the machine, and who sort of became television. We realized that he went through every television format, and that he had his downfall at the same time the world moved on to the internet. It’s as though the internet killed the world and Tapie.”

Séguéla brought another real-world perspective: his father, Jacques Séguéla, was a prominent French publicist, and a friend of Tapie’s. The younger Séguéla has childhood memories of Tapie spending part of his vacations at the Séguélas’ house. “I remember someone who attracted attention,” he says. “And [Tapie] had one quality—I think it’s the same way with the friends of everyone’s parents: There are those who pay attention to kids, and those who don’t notice them. [Tapie] treated everyone equally, adults and children. I liked that, especially since he was already a media monster by the time he came by. I’d see him on TV, and then I’d see him make paella for everyone. And sometimes, we’d quarrel, too. He would argue with me about a bit of the Tour de France, or soccer teams. I liked that too.”

Despite this personal connection, Tapie, before his death, had voiced his opposition to the series. More recently, his family voiced their objections, too. But that was never a problem for Séguéla, nor Lafitte, nor Demangel. They were determined to write the show, and they didn’t particularly want Tapie or his relatives to contribute to the writing. Years ago, Séguéla made it clear to Tapie that he wasn’t seeking his permission to go ahead, Tapie “left him alone” and let him work in peace, Séguéla says.

“It would have annoyed me if he’d felt hurt by the show, if he’d found it insulting or defamatory,” Lafitte says. “But I was comforted by the fact that our work was mainly impartial.”

Despite the differences between Trump and Tapie, the team too had Trump on the mind while crafting the show. “I would even say that Tapie must have had Trump on his mind during his own rise to fame,” Séguéla says. Tapie, Séguéla points out, published a nonfiction book called Gagner (“to win”), a cross between a memoir and a book of business tips. Tapie’s book came out in 1986. Trump’s own book, The Art of the Deal, came out in 1987—three years after Trump appeared on the cover of GQ. The 1984 cover story was titled: “Success: How Sweet It Is. Men Who Take Risks and Make Millions.”

Now, Lafitte struggles to imagine France’s other wealthy men, such as businessmen François-Henri Pinault or Bernard Arnault sing on TV or host a show—both things Tapie did. Still, Tapie’s story as told in the Netflix series seems inseparable from France itself. In Tapie’s tale, Lafitte sees “all the contradictions” of the country’s attitudes to success. “In France, we always tend to be wary of people who succeed materially,” he says. “[Tapie’s story] is the story of a time when the line became a bit more blurry, between [the traditional French mindset] and a more American mindset. He understood that very quickly.”

Read More

Like Harry, they wrote brutally honest memoirs about their families. What happened next?

From Harry Styles to Emma Roberts: How celebrity readers became the book influencers we didn’t know we needed

Slim Aarons started out photographing war – but his greatest assignment was in the trenches of fashion

Hurricane Nigel expected to ‘rapidly intensify’ by Tuesday - latest

Trump says he doesn’t worry about jail risk as he refuses to rule out self-pardon

Front door of home where Sharon Tate was murdered sells for $127k