A man lit a small fire to heat up his coffee kettle. It was a hot and windy day in the countryside outskirts of Argentina’s second-largest city Córdoba. Suddenly, a strong gust of wind stirred the flames and soon there was fire everywhere.

The flames quickly approached Villa Carlos Paz, a sleepy resort town known for its mild climate and views of San Roque lake and the mountains nearby. Locals were filmed throwing buckets of water at the flames from their balconies and hundreds were evacuated. The largest wildfire in the province this year so far burnt for days, kept alive by high spring temperatures of about 37C (98.6F) and strong winds.

pic.twitter.com/bDiVUf4ttP

— Massimo (@Rainmaker1973) October 11, 2023The incident is among many examples of the impacts of a warmer climate, during a year that’s poised to be the hottest on record globally. Over the past few months — during the southern hemisphere’s winter and early spring — extraordinary heat has baked into South America. Climate change, the arrival of the first El Niño in almost four years and mass deforestation, driven by intensive agriculture, are likely to make the continent’s coming summer season even hotter and drier, scientists say.

“We are seeing record heat events in the southern hemisphere and it’s been a warmer winter in parts of Africa and South America compared to previous ones,” said Izidine Pinto, a researcher at the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute. “In the next months, strengthening heat waves are going to intensify in South America — there are more hot days and more heat waves coming.”

Read more: What Is El Niño and How Does it Affect Weather Around the World?

Peru had its hottest winter since record keeping started in 1965, with capital Lima hitting 27.6C (81.68F) on July 5 and temperatures averaging 19.4C and 19.3C in July and August, respectively, according to the country’s meteorological agency. In early August, a heat wave brought temperatures of around 38C (100.4F) in parts of central and northern Argentina and Chile, which is 10 to 20C higher than the average for the height of winter in that part of the world. The unusual heat melted the snow, altering the flow of rivers and water availability in key agricultural regions in Chile.

A second heat wave at the end of August and early September hit a large area that included Paraguay, central Brazil, regions of Bolivia and Argentina. Climate change made the 10-day episode 100 times more likely, according to a rapid attribution study conducted by World Weather Attribution, a network of scientists that applies a peer-reviewed method to determine the influence of global warming on extreme events.

Scientists ran temperature data from the South American heat wave through a model and simulated the same episode in a world without climate change. They found temperatures would have been 1.4C to 4.3C cooler in a world without the warming caused by human emissions of greenhouse gases.

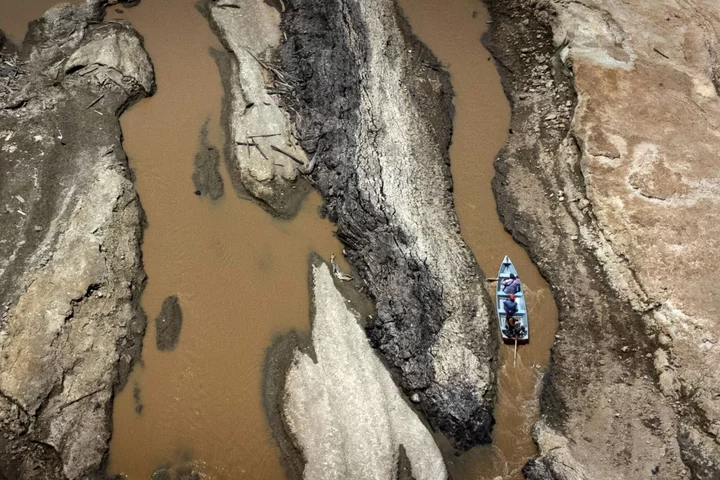

In Brazil, where hydropower accounts for around 80% of domestic power generation, the government is firing up diesel power plants to avert blackouts as drought in the Amazon snarls river logistics and kills river dolphins. A major hydroelectric dam on the Madeira river was shut earlier this month due to low water levels and in the state of Amazonas a combination of illegal deforestation and unauthorized burning activities are intensifying wildfires.

“Deforested land absorbs more solar radiation because it’s bare, with heat accumulating and reflecting back to the atmosphere” Pinto said. “Water accumulates faster in places with no trees or forest, causing more runoff, more erosion and floods.”

A new heat wave brought 45C (113F) temperatures in northern Argentina in October, according to the country’s meteorological agency. In Córdoba, a new round of wildfires has burnt through at least 5,800 hectares. Recently parts of Bolivia, Paraguay and Brazil have continued to see extremely high temperatures.

“Heat is not something new, we had these events in the past,” said Lincoln Alves, a researcher at the Brazil National Institute for Space Research in Sao Paulo and a co-author of the WWA study. “However in the last decades we have seen an increase in the number of events and in the magnitude of these events.”

The influence of El Niño, which is still on its first months, is growing and the region is bracing for its worst impacts in early 2024. But the effects of high heat levels and lack of rain are bound to last much longer.

“Some rivers are already at very low, historic minimum levels; it will probably take time to return to normal values,” said Ana Paula Cunha, a researcher at the Natural Center for Monitoring and Early Warning of Natural Disasters in São José dos Campos, Brazil. “The longer the drought lasts, the more intense the cascading impacts.”

The impact and even the scale of these episodes is vastly underreported, as most countries in South America lack the thousands of weather stations that make it possible for meteorologists to detect heat waves and temperature records in developed countries. Policymakers in the past have also struggled to decisively react to official warnings of El Niño’s impacts, adapt to climate change and mitigate their countries’ contribution to it.

While scarcer financial resources and reliable information have sometimes hampered action, climate-skeptic leaders have slowed down progress too.

In Brazil, the country that holds nearly 60% of the Amazon rainforest, deforestation reached a record high in 2022 during the administration of President Jair Bolsonaro, who sought to loosen economic activities in protected areas and to open indigenous reserves to mining and agriculture. Now, his successor Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva is pledging to end illegal deforestation in the world’s largest rainforest by 2030 and encouraging leaders from other Amazon countries to join.

Argentina is poised to be the next climate battleground in the region. Libertarian outsider Javier Milei, who got around a third of voters’ support on the first round of presidential elections on Sunday, has in the past disputed scientific evidence that climate change is caused by greenhouse gas emissions from human activities, saying global warming is “another socialist lie.”

Milei faces the country’s current Economy Minister Sergio Massa in a runoff on Nov. 19.

--With assistance from Marcelo Rochabrun and Jonathan Gilbert.