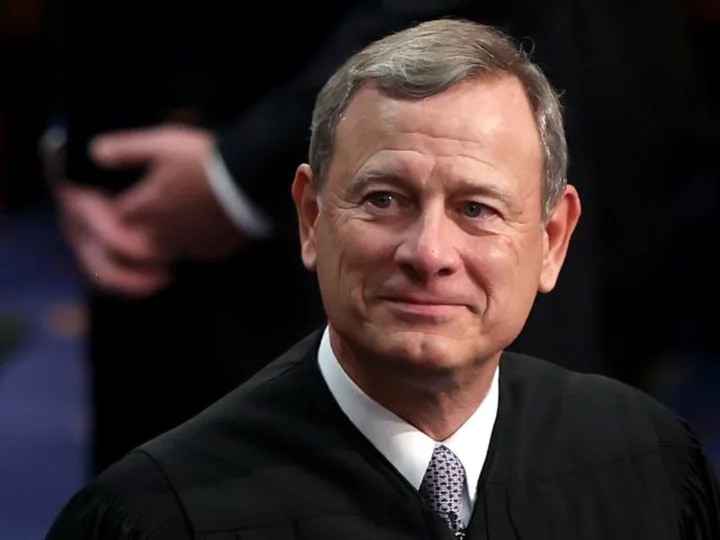

When Chief Justice John Roberts began reading his decision in a voting rights dispute from the Supreme Court bench on Thursday, few would have expected the significant turn he was about to take favoring Black voters in Alabama.

Here was the author of a 2013 decision that had eviscerated a crucial safeguard of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, a jurist who had repeatedly criticized specific efforts to protect Black and Latino voters in redistricting, or as he once called it, "a sordid business, this divvying us up by race."

The court's newest justice, Ketanji Brown Jackson, the first African American woman on the bench, looked down pensively. Only Justice Elena Kagan had her head turned directly toward the chief, sitting at the center of the elevated mahogany expanse, as he began explaining that the key VRA section in dispute was written "to ensure that all voters can participate" in elections.

Roberts then revealed to all what his colleagues knew: He was swerving off a path he had taken for decades, since the early 1980s when he served in the Reagan administration and sought to narrow the reach of the landmark voting-rights law.

Joined by fellow conservative Justice Brett Kavanaugh and the court's three liberals (Sonia Sotomayor, Kagan and Jackson), Roberts affirmed a lower court decision that Alabama had breached the VRA when it devised a congressional districting plan that included only one Black-majority district among seven districts in a state that has a 27% Black population.

Alabama must now adopt a new state congressional map that includes a second Black-majority district.

More importantly, as he defied expectations of civil rights advocates, Roberts maintained a decades-old framework for testing when a state legislature has drawn a racially biased map, diluting the votes of Black citizens, for example, by dividing or compressing the minority population, practices known as "cracking or packing."

Roberts endorsed existing law that takes account of voters' race in redistricting to ensure that the political process is "equally open" to minority voters and that they have a chance to elect candidates of their choice. That will affect other states' litigation over arguably biased maps and upcoming congressional races.

Yet, as dramatic as the Roberts' moment was, it will not be the last word on race this month from the tactical chief justice. His views will be further tested in a pair of college affirmative action cases that threaten court precedent dating to 1978.

The justices are set to resolve by the end of June challenges to practices at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina that consider applicants' race and ethnicity to enhance campus diversity. The challengers have asked the justices to overturn Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978) and Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), credited with expanding opportunities for Black people, Hispanic people and other minorities over the decades but enduringly controversial for allowing racial considerations.

Roberts strongly suggested during oral arguments last October that he wants to end such race-based practices. In a 2007 case involving integration plans in public schools, he wrote, "The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race."

It seems unlikely that Roberts, given his record, would abandon that view wholesale. Roberts will also likely resume burnishing his conservatism as he rules in pending cases, such as those testing religious interests and gay rights, and the Biden administration's authority for the student-loan forgiveness program.

The Alabama dispute offered especially troubling facts on the ground and extreme arguments from state officials. A three-judge lower court had ruled unanimously that under the state legislature's map (drawn after the 2020 census), "Black voters have less opportunity than other Alabamians to elect candidates of their choice to Congress." (On that judicial panel were two appointees of former President Donald Trump, and one of former President Bill Clinton.)

As Alabama officials challenged the revised map, they argued that the benchmark for assessing VRA violations must be "race neutral." Roberts said that would have required the justices to turn their back on nearly 40 years of rulings interpreting the law.

"The heart of these cases is not about the law as it exists," he wrote in his opinion. "It is about Alabama's attempt to remake our Section 2 jurisprudence anew."

In short, the chief justice made plain, Alabama had taken a radical stance at the wrong time.

The Supreme Court has faced fierce public denunciations for recent decisions, especially its reversal of Roe v. Wade and an end to nearly a half century of abortion rights.

It is difficult to know how Roberts -- and Kavanaugh, whose vote sealed the majority in the Alabama case -- have been affected by the intensifying public criticism for the court's boundary-pushing rulings. But they clearly retreated from a pattern that has diminished the ability of racial minorities to challenge practices that undercut the franchise.

Justice Clarence Thomas, writing the lead dissent on Thursday, tossed some of Roberts' previous sentiment back at him. He criticized the Roberts majority for requiring states "to sort voters along racial lines," prolonging "the day when the 'sordid business' of 'divvying us up by race' is no more."

'A call to action'

Roberts, who was serving in 1981 as a law clerk to then-Associate Justice William Rehnquist (who later became chief justice), has said that when he heard Reagan's inaugural address that January, he felt "a call to action."

He soon after landed a job in the Department of Justice. It was at a time that the administration happened to be embroiled in a controversy over the scope of the VRA.

The landmark 1965 law, one of a series of major initiatives of the civil rights era, had been years in the making and passed by Congress only after the "Bloody Sunday" violence on March 7, 1965, when Alabama state troopers attacked voting-rights demonstrators crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma.

Specifically in dispute in 1981 and 1982 was the VRA's Section 2, which prohibits states from adopting election practices that discriminate against voters based on race. Members of Congress at the time wanted to ensure that the provision covered any state action that had the effect of diluting minority representation, irrespective of its intention. (They were reacting to a 1980 Supreme Court ruling that had narrowly interpreted the law.)

As a young lawyer who embraced the administration's "colorblind" approach and opposition to racial remedies, Roberts argued against any "effects test," predicting that it would create a right to a quota-like "proportional racial representation" in districting. (The congressional compromise, eventually endorsed by Reagan, maintained the "effects test.")

Roberts, now age 68, wrote of that 1982 compromise in the Alabama opinion: "Section 2 would include the effects test that many desired but also a robust disclaimer against proportionality."

Notably, Roberts continued his attempts to limit the reach of the VRA once he reached the Supreme Court, appointed by George W. Bush in 2005. He saw the act as a relic of the country's darker days and asserted that it encroached on state interests.

Roberts most consequential ruling came one decade ago this month, when he took the lead as the justices gutted the VRA's Section 5, which required certain states and localities with a history of racial discrimination to clear any redistricting or other electoral change with the Justice Department or a federal court.

"Our country has changed," Roberts wrote for the majority in Shelby County v. Holder, "and while any racial discrimination in voting is too much, Congress must ensure that the legislation it passes to remedy that problem speaks to current conditions."

In the Alabama case, Roberts did not cite the Shelby County v. Holder ruling, although dissenters did, to support arguments favoring Alabama.

In the decade since that decision, Roberts has been part of court majorities that further contracted voting protections, including in 2018 when the justices rejected a challenge brought by Latino advocates to a Texas district that a lower court said denied Latinos an equal opportunity in the political process and upheld an Ohio voter-purge law (for residents who failed to cast a ballot for at least four years).

In a 2021 Arizona case over Section 2 coverage, Roberts and his fellow conservatives raised the bar for claims of racial discrimination. They emphasized states' interest in preventing fraud at the polls and minimized attention to historical conditions of voter discrimination.

So it was easy to understand why observers had predicted that Roberts would shepherd the court toward further encroachment of the Voting Rights Act in the Alabama case.

But reviewing the particulars of the dispute, Roberts endorsed the lower court findings and reaffirmed a standard drawn from a 1986 case, Thornburg v. Gingles.

Among its "preconditions" for Black or Latino voters seeking additional districts is whether their group is sufficiently large and geographically compact; whether the group is politically cohesive; and whether the White majority sufficiently votes as a bloc to defeat the minority's preferred candidate.

The 1986 touchstone dictates that challengers to a redistricting map must demonstrate that the political process has not been "equally open" to minority voters.

As Roberts spurned Alabama's request for a "race-neutral benchmark," he drew a line between being "aware" of racial considerations and "being motivated" by them.

The decision drew the full support of the three liberals. Kavanaugh joined Roberts bottom-line but separated himself from some of his reasoning. He declined, for example, to sign onto Roberts' efforts to distinguish "racial predominance and racial consciousness," and he warned, "the authority to conduct race-based redistricting cannot extend indefinitely into the future."

Dissenters would have allowed the single Black-majority district to stand and curtailed the Voting Rights Act and principles of the 1986 Gingles precedent.

In one of the many barbs directed toward Roberts, Thomas noted that just last year Roberts had written, "Gingles and its progeny have engendered considerable disagreement and uncertainty regarding the nature and contours of a vote dilution claim."

Writing a separate dissent, Justice Samuel Alito added that the Roberts' majority's regard for the 1986 precedent conflicted with "the fundamental principle that States are almost always prohibited from basing decisions on race. Today's decision unnecessarily sets the VRA on a perilous and unfortunate path."

Future cases will test that premise. What is now clear is that Roberts and Alito, previously together to limit the VRA, along with fellow conservatives, have diverged. And that made all the difference for Alabama voters.