Efforts to restructure the debts of the world’s poorest nations are splintering, with a deal between Zambia and its creditors just the latest to hit trouble.

Setbacks have become commonplace in debt talks with defaulted issuers likes Zambia, Sri Lanka and Ghana, raising concern over the next batch of sovereigns whose bond prices are showing distress. The delays are weakening sentiment for developing markets in a year that’s already seen $31 billion in outflows from emerging-market debt funds.

The culprit is a restructuring framework put in place by the Group of 20 three years ago that aimed to help the poorest nations back on their feet during the coronavirus era. But that process has ended up making talks more vulnerable to holdouts, turning negotiations into a tug-of-war between traditional creditors, including the International Monetary Fund and the Paris Club of lender nations, bilateral lenders such as China, and other bondholders.

Geopolitical divisions and varying transparency standards, especially related to China’s rapid expansion into a large lender to emerging nations, have made debt deals more difficult to reach and limited the role of private bondholders.

When Zambia’s government announced earlier on Monday that talks with bondholders had collapsed for the moment, it was “obviously disappointing to private creditors who have been patient with a country such as Zambia for literally years,” said Richard Segal, a London-based fixed-income analyst at Ambrosia Capital Ltd. “This is the first instance I am aware of where an agreement with one group of creditors has been effectively vetoed by another.”

The development comes after Zambia, which defaulted in 2020, reached a memorandum of understanding last month with “official creditors” — meaning, essentially, other sovereign governments that had lent it money — to restructure $6.3 billion of debt.

The southern African nation needed to receive treatment at least as favorable from private creditors under the G20’s Common Framework guidelines. So it agreed on revised terms with bondholders, but those were rejected by official creditors on Monday. Lazard Ltd., the financial adviser to Zambia, declined to comment.

Yvette Babb, a portfolio manager at William Blair B.V based in The Hague, said the Common Framework, which was designed to confront fears of a liquidity crunch in the pandemic era, has injected an additional level of complexity into such talks. In Zambia’s case, disagreements among official creditors appear to be delaying the restructuring, she said.

“The negotiations are taking such a large amount of time, and they don’t only affect Zambia or Ghana but the whole asset class,” Babb said. “This creates questions on the speed of restructuring of other distressed assets, and if they may be able to reach a conclusion.”

The upshot of Zambia’s woes is that they “will make eurobond sales by low-income countries close to impossible without at least partial guarantees,” Ambrosia’s Segal said.

‘Completely Undermine’

The rejection of the revised Zambia deal by official creditors will “completely undermine the already diminishing credibility of the Common Framework,” the steering committee of bondholders said in reaction to the news on Monday. “It is not for official bilateral creditors to dictate debt terms to other creditors in circumstances where the government has confirmed comparability of treatment.”

In a report from June, analysts at JPMorgan Chase & Co, led by Ben Ramsey, said they have long been skeptical about restructurings where the official sector takes the lead in defining and imposing the terms.

China generally differs from multilaterals in lending at higher interest rates but making no requirements for economic or political reforms on the emerging markets receiving the loans, JPMorgan said. Furthermore, the terms of its loans often aren’t public, making the implementation of any “fair treatment” principle difficult to assess.

“Even if the official sector can eventually get on the same page, the private sector including bondholders may disagree with what assumptions are being made about the losses they take,” Ramsey wrote.

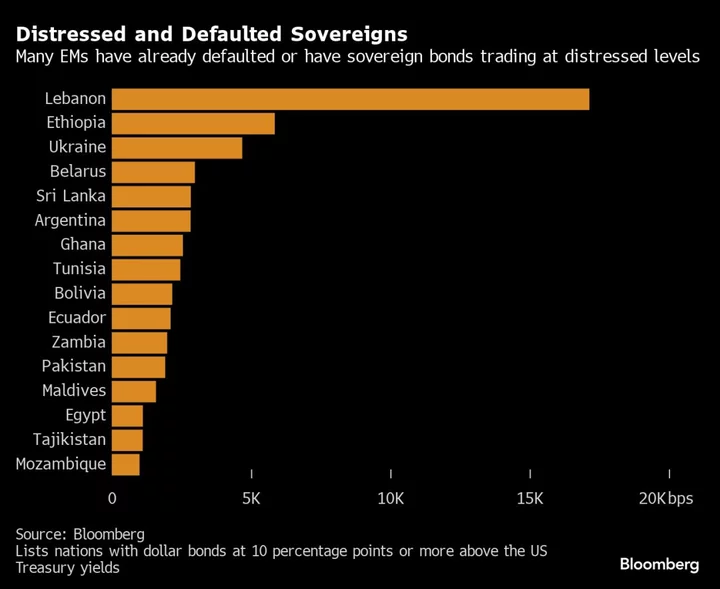

Talks with Sri Lanka and Ghana are also dragging on, while expectations for higher-for-longer interest rates in the US are making borrowing difficult — or impossible — for the poorest emerging-market sovereigns. Dollar bonds of 16 developing nations currently trade at a spread of at least 1,000 basis points over similar Treasuries, a common definition for “distress,” according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The prolonged debt restructurings are clouding the outlook for emerging markets at a time when high global interest rates have already curbed appetite for the asset class, said Trang Nguyen, global head of emerging-market credit strategy at BNP Paribas SA in London.

“It would be different if it was just a one-off, but actually we have multiple debt restructurings that are happening concurrently, all with varying degrees of delays, and that has been a really dampening factor for the asset class overall especially when cash gives you 5%,” she said, referring to US Treasury yields.

That all marks a change from restructuring deals in the recent past, with Argentina and Ecuador completing negotiations with private creditors in less than a year in 2020. They were processes in which bilateral creditors weren’t involved.

“One major inefficiency of the Common Framework is that private creditors are excluded from the negotiating table and are presented with a fait-accompli,” said Simon Quijano-Evans, the chief economist at Gemcorp Capital Management Ltd in London. “The G20 need to explain how that can be good for anyone, whether debtor or creditor.”

--With assistance from Matthew Hill.