Days after pitching Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s governing coalition into an unprecedented budget crisis and sending shockwaves rippling through Europe’s biggest economy, a press officer at Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court said all was quiet and back to business as usual.

The calm at the guardian of the country’s Basic Law is a marked contrast to the turmoil in Berlin and reflects the self-confidence of an institution that has the standing and independence to exercise sway far beyond Germany’s borders. While the glass walls of the 1960s courthouse in Karlsruhe — a quiet city, far removed from the political wrangling in the capital — are intended to symbolize transparency, that’s not entirely the case.

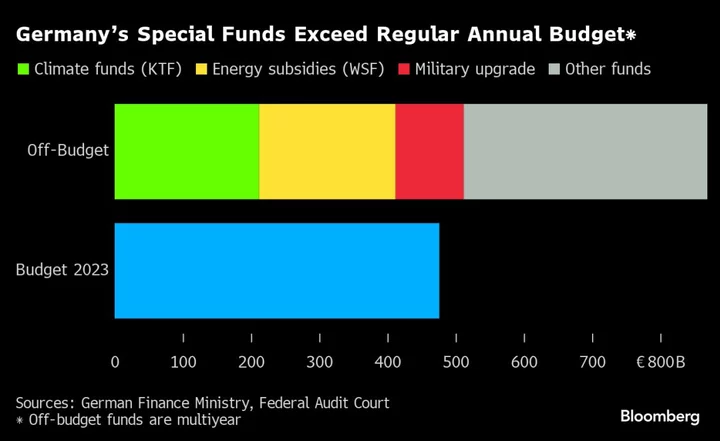

The bombshell judgment, which called into question Germany’s use of special funds containing hundreds of billions of euros, prompted Finance Minister Christian Lindner on Thursday to back off a key political promise and announce that Germany would suspend a constitutional limit on net new borrowing in 2023. The convulsions have roiled markets and raised questions about how Germany can continue to invest in the overhaul of its economy.

While the tribunal has won a reputation as a defender of individual liberties, it’s also spread unease as its rulings often touch the tender line between interpreting Germany’s constitution and interfering with politics. Following the budget ruling, newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung commented that the judges were setting a dangerous course by playing a role in governing.

In the case that forced the government to overhaul off-budget funding tools, Justice Sibylle Kessal-Wulf was in charge of drafting the judgment. The former civil-court judge — who was nominated by the Christian Democrats, which filed the complaint — managed to convince enough judges to get this result, but it’s unclear whether the decision was unanimous. Unlike in many other cases, the court didn’t disclose how the eight judges voted and no dissenting opinion was published.

Another key justice was likely Peter Müller, a card-carrying member of the Christian Democrats. The former premier of the state of Saarland earlier this year surprised court observers by criticizing the “breathtaking” debt piled on by Germany and the European Union in recent years, and even attacked the special funds now put in question by the ruling. He did so in a speech at a CDU party event, while the debt case was pending before his panel. The government could have tried to have him removed from the case for bias, but didn’t file such a request.

Both Müller and Kessal-Wulf are reaching the end of their 12-year terms, which can’t be renewed. On Friday, Peter Frank — another nominee of the conservative alliance and the former Federal Prosecutor — was elected to replace Müller.

A court press officer said the tribunal doesn’t have to disclose further details of the decision-making process and declined to comment further.

When West Germany approved its constitution in 1949, the constitutional court was added. Modeled in part after the US Supreme Court, it was put on the same level as the government and parliament, with powers to review and strike down laws.

While nominating justices is a political process, it’s not accompanied by the public hearings and media frenzy seen in the US. Few of Germany’s top judges — who wear traditional satiny red robes in court — are widely known.

They’re picked in a somewhat obscure fashion that’s agreed upon among the main parties in parliament. Approval needs a two-thirds majority in one of the legislative bodies, which requires cross-party support and leads to a bench that’s less prone to ideological divisions.

The justices see the tribunal as “the people’s court,” and anyone can file a case without a lawyer, but of the 5,361 individual complaints ruled on in 2020, only 111 succeeded. Still, the sheer opportunity has helped maintain its reputation, with the court regularly scoring the highest approval and trust ratings of all government bodies by a wide margin in polls.

The court started to operate in 1951 and soon thereafter established its independence. A famous early example was a ruling that thwarted a plan by Konrad Adenauer to set up a government-run national TV station. Germany’s first chancellor was said to have commented: “That’s not what I had in mind” with the court.

Landmark rulings on freedom of speech, equality and other fundamental civil rights have further bolstered its reputation, and “I’m going to Karlsruhe” has become a popular German phrase to express the possibility of redressing injustice.

The constitution grants the justices jurisdiction over a wide range of disputes and most political conflicts in Germany sooner or later end up before the Constitutional Court. Due in part to the volume of cases, there are two panels of justices, called Senates, each with eight members.

Read More: Merkel’s Conservatives Suffer Climate Setback After Court Rebuke

The First Senate mainly hears cases involving individual rights. The Second Senate, which ruled on the budget funding, has jurisdiction over disputes between branches of government and those involving the relationship with the European Union.

Despite political influence in the appointment process, no justices vote strictly along party lines. That was palpable during the financial crisis when almost every step to rescue the euro landed before the judges. The conservative Peter Huber and Social Democratic Andreas Voßkuhle — which are no longer on the court — worked together to close ranks in these rulings.

While then-Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government formally won all these cases, the judges regularly voiced objections over the massive debt the steps entailed and attached strings and aimed to give the national parliament more say. These cases came to be known as “yes, but” rulings.

The only complaint granted was a 2020 judgment against the European Central Bank’s bond-buying program. That decision almost caused an EU crisis because the justices declined to follow precedent set by the bloc’s top court. But the German judges allowed the ECB a back door by giving it three months to justify its moves.

A “yes, but” approach was also expected in the case alleging the government was breaching constitutional borrowing limits, known as the debt brake, according to Oliver Lepsius, a law professor at Münster University.

“But it didn’t work this time,” he said. “It looks like the end of the crisis justification.”