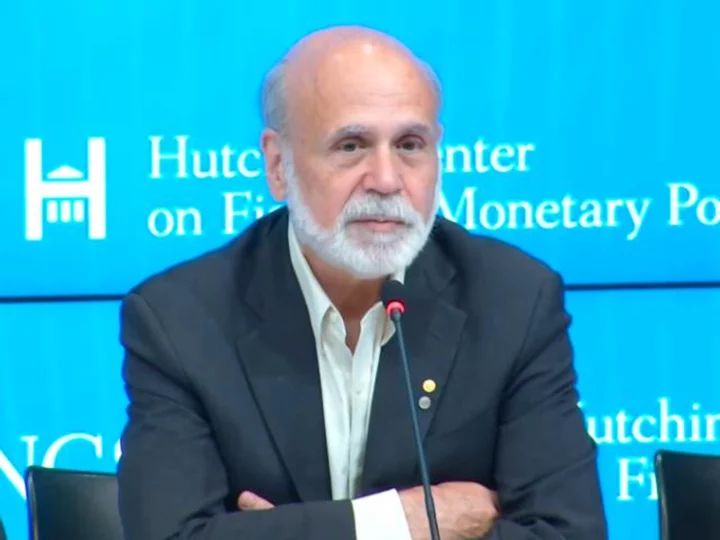

Former Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke, who steered the central bank during the Great Recession, argued in a newly released paper that the Fed still has more work to do to bring inflation down.

"Looking forward, with labor market slack still below sustainable levels and inflation expectations modestly higher, we conclude that the Fed is unlikely to be able to avoid slowing the economy to return inflation to target," Bernanke and Olivier Blanchard, a former International Monetary Fund chief economist, wrote in the paper released Tuesday.

Inflation has cooled in the past several months, according to the Fed's preferred inflation gauge and the Consumer Price Index, though some Fed officials have said that it's not cooling fast enough. The new study co-authored by the former Fed chair argued that the labor market has become a larger contributor of inflation, and might prove to be a stubborn source of price pressures that might only be remedied by an economic downturn.

Indeed, the labor market remains on strong footing. Employers added 253,000 jobs in April and average hourly earnings rose by 0.5% that month. Jobless claims remain relatively low — though they have trended up in recent weeks — and job openings still exceed the number of unemployed people seeking work.

"Overheating in the labor market has played a minor role but an increasing one over time. As price shocks fade, it is likely to be the dominant factor, requiring a slowdown of the economy to return inflation to target," Bernanke and Blanchard wrote in a slide show of their paper presented at a forum hosted by the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC.

The paper analyzed the causes of inflation's ascension in 2021 and how it has evolved since.

Inflationary pressures began in the goods market that year as commodity prices spiked and American consumers, flush with stimulus payments at the time, dealt with the goods shortages, according to the study. Overall inflation crept up throughout that year, then the Fed began to raise interest rates in March 2022 from near zero.

The central bank has seen some progress since raising interest rates 10 times in a row, though bank stresses emerged earlier this year as inflation slowed, raising some concerns over the effects of the Fed's aggressive rate hiking campaign. Despite the failures of three regional banks since March, the Fed still raised interest rates two more times during that period.

After officials voted unanimously to raise the central bank's benchmark lending rate by a quarter point earlier this month, they indicated in their post-meeting statement that a future pause in rate hikes is now a possibility.

But some Fed officials have indicated in recent speeches and interviews that they're not yet convinced that inflation is on a certain path toward the central's banks 2% target, intensifying the debate over raising rates again or pausing.

Data gauging the state of the labor market in coming weeks and a CPI report during the Fed's two-day meeting in mid-June will further inform officials on whether to opt for an additional rate hike or a pause. Officials will also be taking into consideration credit conditions and the lagged effects of tighter monetary policy, which could further dampen demand.

Mary Daly, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, said during a conference on Monday that the time when rising interest rates begin to notably impact the broader economy "is getting nearer and we have to be extremely mindful that that built up slowing is already in the chain could start to show through at any point in time."

"And when you add the credit tightening that we've been seeing to that, it means that there's a lot of factors pulling back the reins on the economy and that's why we have to be so critically data-dependent, because if we think it's not here yet and then we tighten too much, we can easily create an unforced error where we've over tightened," Daly, who isn't currently voting on interest-rate decisions, said.