The man who runs the bank widely seen as the European champion-in-waiting has all he needs to take center stage with a major merger.

Jean-Laurent Bonnafe has built an $8.3 billion war chest and the biggest corporate and investment bank in Europe in his 12-year stretch atop BNP Paribas SA. The CEO has seized on rivals’ stumbles and cost-cut his way to record earnings, and he has extensive knowledge of how to pull off the cross-border marriages that every bank executive says must happen to compete with the encroaching American giants.

But facing shareholders in the vast convention hall under the Louvre Museum in Paris last month, Bonnafe summed up the odds of him doing such a deal: “close to the absolute zero.”

The reserved and meticulous chief executive officer would know the pitfalls. He rose through BNP’s ranks by integrating the huge mergers of his predecessors. His own reign has been marked by smaller deals, consistent results and the perfectly timed sale of US regional lender Bank of the West that closed just before that industry was thrown into chaos.

Bonnafe’s aversion to a major acquisition closes off one path for transformative growth at a time when investors look ready for something more dramatic. Since doubling in Bonnafe’s first two years in office, the shares have moved sideways over almost a decade. And despite being the most profitable bank focused on Europe and promises of steady growth and more buybacks, BNP Paribas now trades more than 40% below its book value, a bigger discount than the average for major European banks.

Bonnafe has made “disciplined growth” his brand while rivals lurched from one crisis to the next. Now, BNP Paribas faces the question of what’s next — and whether that title as European champion-in-waiting will become a permanent moniker.

“Bonnafe’s growth plan could use more clarity,” said Jerome Legras, managing partner at Axiom Alternative Investments. “The next 18 months are crucial for the bank, as we’ll see if they manage to invest the proceeds from the Bank of the West sale into projects with higher profitability.”

Legras said he doesn’t expect Bonnafe to do a big deal, but rather keep diversifying and building up businesses where the bank can benefit from scale effects, like insurance. Bonnafe declined to comment for this story.

To be fair, European bank stocks overall haven’t done well since the financial crisis, and BNP’s performance is still better than that of most peers. The stock is up 91% since Bonnafe took over in December of 2011, compared with 30% for local rival Societe Generale SA. Barclays Plc declined 11% and Deutsche Bank AG lost 62% over the period. Credit Suisse Group AG no longer exists as an independent firm.

All those rivals repeatedly shocked investors with steep losses over the past years. Not so Bonnafe, who posted a predictable profit in every quarter except one (in 2014, when he agreed to a historic $9 billion penalty after the bank violated US sanctions). Analysts agree that Bonnafe has done a good job managing risk and balancing opportunistic deals with conservatism.

“BNP has been avoiding the landmines that blew up its competitors,” said Matthew Clark, an analyst at Mediobanca. “It kept delivering consistent earnings across its various franchises, enabling it to stack up capital.”

That’s made BNP Paribas one of the few firms strong enough to step in as buyer when rivals had to shed businesses. In 2019, it agreed to take over Deutsche Bank’s prime brokerage business as the German lender retreated from equities trading as part of its restructuring. Soon after, Bonnafe picked up the hedge fund clients of Credit Suisse as that firm sought to become less risky following a $5.5 billion loss from its dealings with Archegos Capital Management.

BNP Paribas also bought the remaining stake it didn’t already own in Exane SA to build out its equities platform, in a wager that the combination of research and prime brokerage will lure clients, including in the US.

“By taking over a top tier platform, we saved about a decade of technology developments,” says Yann Gerardin, BNP Paribas’s chief operating officer who also runs the investment bank, about the Deutsche Bank deal. The firm is now targeting the top spot in Europe in equities trading.

The deals in prime brokerage — the profitable but risky business of facilitating the often highly leveraged trades of hedge funds — have strengthened BNP Paribas’s markets unit as it competes with Barclays and Deutsche Bank for the top spot in Europe. Its corporate bank already ranks first in arranging European bonds this year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

“BNP is the last man standing in European investment banking,” said Clark. “While Barclays retains a large franchise in FICC trading, others such as UBS, Credit Suisse, SocGen or Deutsche Bank all cut back their business over the years.”

That role as one of the last financial supermarkets in Europe, coupled with its financial strength — BNP has one of the biggest balance sheets among banks in Europe — has invited comparisons with Wall Street giant JPMorgan Chase & Co. In addition to its top-ranked corporate and investment bank, BNP Paribas also boasts extensive commercial and retail banking operations, from France, Belgium and Italy to China, where it targets corporations and wealthy clients. Its insurance arm Cardif operates in more than 30 countries in Europe, Asia and Latin America, making €30 billion in gross written premiums last year.

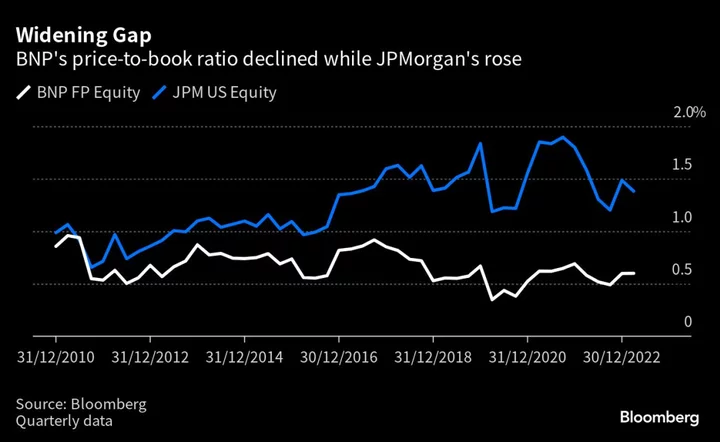

Yet if BNP is the closest Europe has to a JPMorgan Chase, its stock market valuation is a long way off. At about €68 billion, it’s worth less than a fifth of what its US rival fetches. Its price-to-book ratio, at 0.6, is just below the average of 0.62 for the Stoxx 600 Banks Index. JPMorgan, like most of the large US firms, trades at a premium to book value.“BNP is a well-managed bank” with “a diversified business model that allows for a steady growth,’’ said Flora Bocahut, an analyst at Jefferies Financial Group Inc. “Still, this doesn't show in the bank’s share price.”

Indeed, if JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon epitomizes the swashbuckling Wall Street banker, Bonnafe is very much the opposite. A graduate of the Polytechnique engineering school who fast-tracked his career at the Corps des Mines where the French administration recruits top civil servants, he is deeply entrenched in the country’s elite. He joined Polytechnique the same year as French Prime Minister Elisabeth Borne and rubbed shoulders there with Frederic Oudea and Tidjane Thiam, who both went on to run major European banks.

A former colleague, who asked not to be identified discussing his personal views, describes Bonnafe as a hard-working technocrat focused on execution and results. Employees nickname him “J-Lo” for the initials of his first name, but he isn’t a socialite. With the exception of the Paris Opera, where he chairs a group of supporters, or the French Open at Roland-Garros Stadium that BNP has sponsored for 50 years, he usually stays out of the spotlight.

At town halls and shareholder meetings, he has recently tended to dress down, breaking from the traditional more formal attire. He rarely loses his temper, even when shareholders quiz him about deals as they did in May. Having spent some of his military service in a nuclear submarine, he compared major takeovers to quantum-like situations that present themselves too rarely to make them a growth strategy.

“Everything can always happen at some point or another of a company’s history,” he said, wearing his trademark zip-up cardigan. “But when we’re thinking of strategy, we cannot have a strategy based on an event whose likelihood is close to the absolute zero.”

Another former colleague, who also asked for anonymity to discuss his private views, agreed there wasn’t much to acquire for Bonnafe in recent years, and that the transactions he did make were all focused and smart. But, this person said, BNP Paribas wasn’t built through small bolt-on deals, and Bonnafe is now sitting on a massive war chest that is waiting to be deployed.

The deteriorating economy “is going to create opportunities for those like BNP, who have the ability to take on market share when competitors withdraw, or even take up parts or entire institutions at good price if they fail,” said David Knutson, investment director at Schroders Plc.

Throughout its history stretching back as far as 1822, BNP Paribas has been at the center of mergers and acquisitions in France’s banking industry. In its current form, it was created through the 2000 combination of Banque Nationale de Paris and Paribas under former CEO Michel Pebereau. Europe had established a single market for goods and services a few years earlier, and Pebereau was looking to build a bank for that new reality.

Bonnafe was still in his thirties when he was given the job of overseeing that deal. It was a lesson in how to combine two culturally very different firms, with BNP focused on retail and corporate clients, while Paribas was providing investment banking services to a more institutional client base.

The deal made Bonnafe the go-to person for subsequent transactions. When BNP Paribas took over Banca Nazionale del Lavoro in 2006, he was in charge of integrating it, shuttling between Paris and Rome and learning Italian at night. Soon after, BNP completed its last large transaction with the purchase of Fortis’s operations in Belgium and Luxembourg at the peak of the financial crisis under CEO Baudouin Prot. Once again, Bonnafe played a key role, spending time getting to know clients in the Dutch-speaking north of Belgium, a region whose economy relies heavily on its ports.

His role in the Fortis deal set up Bonnafe to take over as CEO when Prot became chairman. The purchase had made BNP Paribas a true European bank and underscored its ambition as a potential acquirer in a cross-border consolidation. But while his predecessors liked to indulge in deal scenarios — Pebereau in his resignation speech as chairman made no secret of his interest in firms such as Societe Generale or Credit Lyonnais during the 1990s — Bonnafe remained reluctant to talk about takeovers.

Speculation about the need for bank consolidation in Europe has been rampant since the financial crisis, but actual deals have been rare, particularly cross-border takeovers. That’s because the lack of a common deposit insurance and onerous capital rules didn’t make them attractive. The latter were softened last year, a change that was particularly positive for BNP.

Read more: European Banks Led by BNP to Benefit From Basel Rule Change

Political considerations remain a major hurdle. When Credit Suisse teetered on the brink in March of this year, the Swiss government quickly brokered a national solution that saw the lender collapse into the arms of cross-town rival UBS Group AG. BNP Paribas had been exploring which parts of Credit Suisse might be a match, part of its routine assessment of strategic opportunities, according to people familiar with the matter. In public, Bonnafe downplayed any suggestion that he was interested in the lender.

The deal reinforced a perception that the window for cross-border consolidation in Europe was perhaps closing again before it had properly opened. Banking had become a highly political subject after governments bailed out lenders in the financial crisis, and national authorities again stepped in with billions in guarantees during the pandemic. With so much taxpayer money at stake, handing a domestic lender to a foreign rival would be a hard sell.

Politics had complicated similar situations before. BNP Paribas reportedly held talks in 2017 about buying the German government’s stake Commerzbank AG. Two years later, Berlin instead decided to promote merger talks with Deutsche Bank that ended up going nowhere. Or take ABN Amro Bank NV, another lender that still counts the government as shareholder. BNP was among banks expressing interest, but the Dutch never seriously examined it, Bloomberg reported previously. BNP recently denied having shown interest in ABN Amro.

At other times, it was Bonnafe who walked away. Before SocGen entered into talks with AllianceBernstein to set up a joint venture in cash equities and research last year, BNP Paribas was given the opportunity to assess the unit but decided against a deal, people familiar with the situation said. It also cooled on Credit Suisse’s securitized products group after looking at it when that business came to the market last year, Bloomberg reported at the time.

In another sign that Bonnafe is ready to give up size in favor of shareholder returns, he sold US retail lender Bank of the West, a Californian bank that BNP had owned since the late 1970s. Bonnafe decided to divest because the cost of participating in a consolidation overseas while BNP’s own equity was still below book value would have been difficult to explain to shareholders.

Bank Chaos Opens Capitalism’s New Era: Micklethwait & Wooldridge

The timing of the $16.3 billion sale, which closed in February, couldn’t have been better. Shortly after, the troubles of several regional US lenders including Silicon Valley Bank triggered a banking crisis. JPMorgan stepped in to acquire one of them, First Republic.

Bonnafe has made it clear that he plans to use a large part of the proceeds from the Bank of the West sale for shareholder distributions, leaving about €7.6 billion for takeovers and investments in existing businesses. Recently, he invited division heads to pitch new investments, a person familiar with the plans said.

“The bulk of our investments will be focused on organic growth, through immediate new businesses such as new clients, that keep our margins intact,” Chief Financial Officer Lars Machenil said in an interview. “The remainder will be allocated to bolt-on deals, either to take over units or portfolios that our competitors want to dispose of, should they complement our offer, or to acquire some technology.”

Among the areas the bank could beef up is asset management. With €526 billion overseen for clients at the end of March, it’s dwarfed by the nearly €2 trillion at rival Amundi SA, which nearly doubled its assets under management through a string of acquisitions since its initial public offering in 2015. BNP’s insurance arm is weighing a bid for the life insurance operations of Indonesia’s PT Astra International.

“BNP is underexposed in asset management, and there are reasons to believe that the bank may have missed external growth opportunities in that space over the last decade,” said Clark at Mediobanca.

But deals are no strategy, and so Bonnafe for now remains focused on what he’s so successfully done over more than a decade. He has set a goal for an additional €2 billion in savings through 2025. He’s also giving up some of the bank’s historic buildings in central Paris and moving staff to the outskirts. That’s after he already reduced branches and moved back office operations to countries like Portugal.

“This is not the Olympic Games,” Bonnafe told Bloomberg Markets Magazine in an interview five years ago. “This is banking. Banking is about history and numbers. It’s an industry in which you have to survive the cycle. You have to have the ability to go through cycles and deliver a full scope of services in a number of geographies. Anything else is just funny, it’s just being ‘brilliant.’ It’s not banking.”

--With assistance from Reinie Booysen and Stephanie Davidson.