An appeals court has ruled the state of Alabama cannot execute an intellectually disabled man who was sentenced to die for murdering a man in 1997, upholding a lower court's decision.

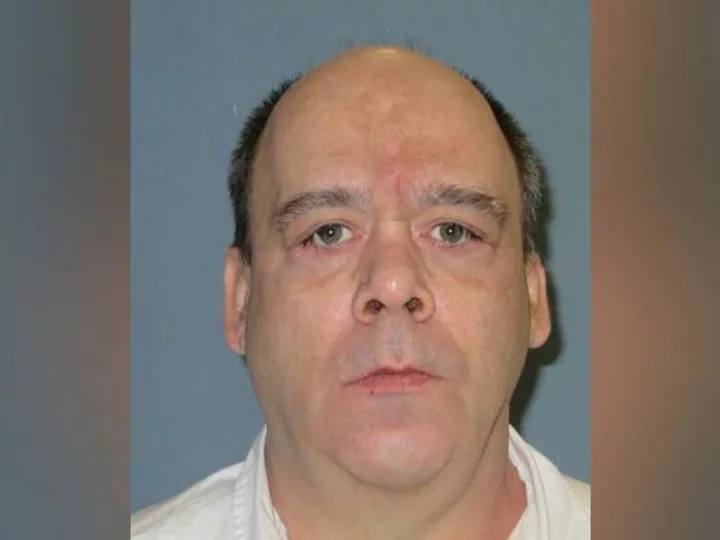

The US Eleventh Court of Appeals' decision on Friday means that 53-year-old Joseph Clinton Smith cannot be executed unless the decision is overturned by the US Supreme Court.

In a statement released after the appeals court decision, Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall said "Smith's IQ scores have consistently placed his IQ above that of someone who is intellectually disabled. The Attorney General thinks his death sentence was both just and constitutional."

"The Attorney General disagrees with the Eleventh Circuit's ruling, and will seek review from the United States Supreme Court," the statement continued.

In 2021, a US District Court judge ruled that due to his intellectual disability, Smith could not "constitutionally be executed," and vacated his death sentence.

The judge referenced the district court's finding that Smith's "intellectual and adaptive functioning issues clearly arose before he was 18 years of age," according to the appeals court ruling, which agreed with the lower court.

Court cites struggles in childhood, at school

Smith confessed to murdering Durk Van Dam, whose body was found "in an isolated area near his pick-up truck" in Mobile County in southwest Alabama, according to the order. Smith "offered two conflicting versions of the crime," the order says -- first admitting he watched Van Dam's murder and then saying he participated but didn't intend to kill the man.

The case went to trial and the jury found Smith guilty, the order states. During his sentencing proceedings, Smith's mother and sister testified that his father was "an abusive alcoholic," according to the order.

Smith had struggled in school since as early as the first grade, the order says, which led to his teacher labeling him as an "underachiever" before he underwent an "intellectual evaluation," which gave him an IQ score of 75, the court said. When he was in fourth grade, Smith was tested again and placed in a learning-disability class -- at the same time as his parents were going through a divorce, the court said.

"After that placement, Smith developed an unpredictable temper and often fought with classmates. His behavior became so troublesome that his school placed him in an 'emotionally conflicted classroom,'" the order states.

Smith then failed the seventh and eighth grades before dropping out of school entirely, the order says, and he then spent "much of the next fifteen years in prison" for burglary and receiving stolen property.

One of the witnesses in Smith's evidentiary hearing held by the district court to determine whether he's intellectually disabled was Dr. Daniel Reschly, a certified school psychologist, the order says.

Reschly testified that the medical community defines intellectual disability as deficits in intellectual and everyday skills in areas such as literary, financial and language -- but also when those qualities arise at an early age, the order states.

The court ultimately determined that Smith "has significant deficits in social/interpersonal skills, self-direction, independent home living, and functional academics," the order says.

In its conclusion, the appeals court wrote: "We hold that the district court did not clearly err in finding that Smith is intellectually disabled and, as a result, that his sentence violates the Eighth Amendment. Accordingly, we affirm the district court's judgment vacating Smith's death sentence."

"This case is an example of why process is so important in habeas cases and why we should not rush to enforce death sentences—the only form of punishment that can't be undone," the office of Smith's federal public defender said in a statement after the appeals court decision.

"Originally, this same District Court denied Mr. Smith the opportunity to be heard, and it was an Eleventh Circuit decision that allowed a hearing that created this avenue for relief," the statement said.