When a seam joining two segments of the Keystone oil pipeline ruptured on a frigid night last December — spewing more than 12,000 barrels of heavy crude that polluted a Kansas creek — the disaster had already been years in the making.

More than a decade ago, US regulators warned that the type of weld that would go on to trigger the worst spill in Keystone’s history had a pattern of failure. And since Keystone began operation in 2010, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration has notified operator TC Energy Corp. at least five times that elements of Keystone’s building and operating practices posed safety risks.

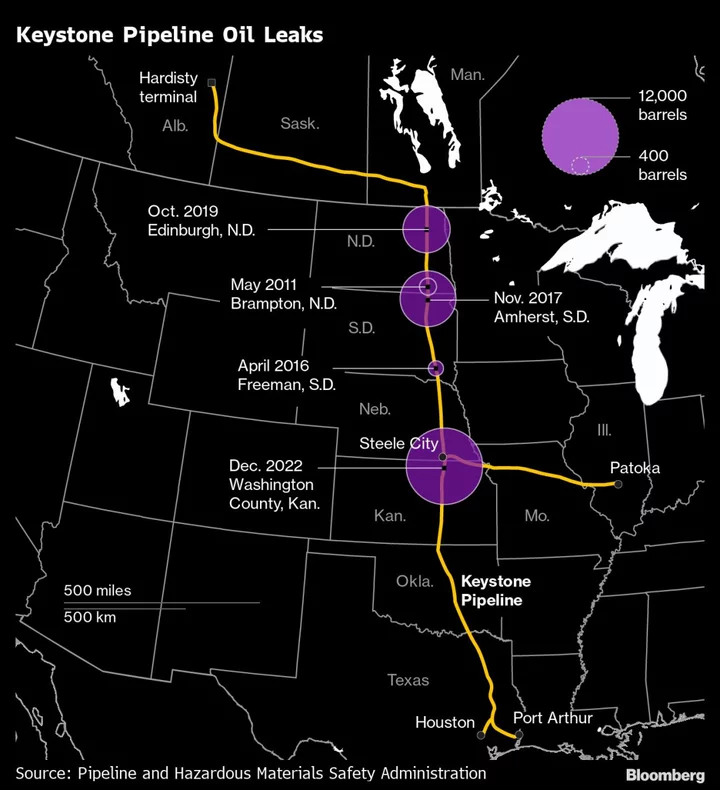

Yet the 2,687-mile (4,324-kilometer) pipeline running from Canada’s oil sands through America’s heartland has gone on to suffer almost two dozen accidents in 12 years, with the severity of leaks increasing over time, according to the Government Accountability Office. Since 2010, it has spilled more oil than any other pipeline on US soil, PHMSA data show.

Government records reveal TC Energy pushed the pipeline to the limit, cranking a measure of stress on the line higher than what’s typically allowed to move more oil while keeping costs down. US regulators signed off on all of it and — even as they warned of danger — refrained from taking maximum enforcement action to curb worsening spills. Now, as the disruption of global energy flows by Russia’s war in Ukraine revives political will and investor appetite for new US pipelines, Keystone’s record stands as a stark reminder of the risks such systems can pose.

“Some pipelines run for decades without incident,” said Richard Kuprewicz, president of Redmond, Washington-based consultancy Accufacts Inc., which provides technical expertise to regulators and companies. “The fact that they have had numerous ruptures, it suggests that something isn’t quite right here.”

TC Energy maintains that the pipeline “has met or exceeded all regulatory and code requirements in the jurisdictions where we operate.”

“While no safety incidents are acceptable to us,” the company said in response to questions, “when they have occurred, we have ensured a fulsome response that fully remediates the environment and considers all stakeholders and their impacts.”

PHMSA, in response to questions, said it’s investigating whether TC Energy has violated any pipeline safety regulations and “will appropriately issue enforcement or compliance actions to hold the responsible party or parties accountable.”

Agency records detail Keystone’s long history of construction issues and allege the company failed to employ adequately qualified workers, perform mandatory risk assessments and take steps to prevent corrosion. Only two other operators — Enterprise Products Operating LP and Tennessee Gas Pipeline Co., which both manage pipeline systems much larger than Keystone — have accrued more so-called corrective action orders. Enterprise and Tennessee Gas didn’t respond to requests for comment.

In many ways, Keystone is one of a kind — built with special authorization to operate outside the bounds of existing US pipeline rules.

First, TC Energy sought permission to use a thinner but purportedly stronger type of steel than is normally allowed, which the company said would cut costs, according to an investigation by the Government Accountability Office, called the GAO. And the company wanted permission to run the line at a higher stress level than any other US oil conduit – requesting to operate at 80% of its so-called “specified minimum yield strength,” or SMYS, versus the 72% typically permitted. That would enable Keystone to transport more oil without increasing its size.

US regulators granted both requests. Problems emerged soon after.

In 2008, the same year Keystone began construction, federal inspectors identified quality issues with pipe manufactured by companies that supplied TC Energy and other pipeline operators, according to the GAO. Certain pipe didn’t meet strength requirements, and was found to deform when operated at certain pressure. PHMSA ordered TC Energy, as well as other companies, to inspect affected pipelines and replace segments as needed, an effort that took years, according to the Government Accountability Office.

The agency also required Keystone to operate at a reduced SMYS, or stress level, when it started service in June 2010.

Soon after that, inspectors discovered that a certain type of pipeline joint called a girth weld had a tendency to fail when connecting pipes of different thicknesses. One such failure occurred during a hydrostatic test on a Keystone segment in South Dakota. PHMSA went on to issue an industry-wide safety advisory about such welds. In the years to come, more spills would be attributed to failed welds, including the more-than 12,000-barrel incident last December, and a number of incidents on other pipelines.

Read more: Keystone Has Leaked More Oil Than Any Other Pipeline in US Since 2010

The pipe quality and girth weld issues identified by PHMSA were not unique to Keystone. Yet, the pipeline’s accident record from 2015-2020 was worse than the nationwide average, according to the GAO investigation. And between 2010 and 2020, half of Keystone spills impacting people or the environment were caused by “material failure of pipe or weld,” the GAO said. That compares with 12% for all other pipelines.

In response to questions about past spills, TC Energy said, “We have analyzed root causes, implemented remediation plans, and integrated the learnings in our engineering and integrity programs with each issue.”

Keystone’s first leaks were small, according to government records. But, in 2011, a 400-barrel spill in North Dakota drew regulators’ attention again. The rupture was caused by a broken fitting, according to PHMSA, which then took a closer look at the line. Two years later, the agency sent a letter to TC Energy alleging that the company had hired unqualified welders on the line’s Oklahoma-to-Gulf Coast segment – which was still under construction – and that a significant proportion of welds on the section would require repair. TC Energy challenged those findings, saying it had complied with regulation and had “addressed the welding issues that occurred.” PHMSA posted TC Energy's challenge on its website but didn’t post any record of resolution. TC Energy declined to comment.

PHMSA would continue issuing safety warnings, and also greenlight Keystone’s expansion plans.

First the line expanded to the US oil hub of Cushing, Oklahoma, and later to the US Gulf Coast. Some of the pipeline segments were found to have expanded under pressure, and 32 joints had to be replaced in 2016, according to the Government Accountability Office. Later that year Keystone was also allowed to ramp up to 80% of its SMYS.

Around this time, Keystone’s oil spills became more severe, records show. Another 400-barrel leak in South Dakota was found to be the result of a faulty girth weld between two segments of different thickness. The weld had been leaking about two drops of crude oil a minute for an unknown amount of time, according to the agency.

A year later, another rupture in South Dakota released some 5,000 barrels of oil, leading to a nearly two-week shutdown. Two years later, more than 4,000 barrels spilled in North Dakota, with the rupture traced to an “atypical seam weld.”

Even as federal warnings multiplied and the size of the spills increased, the Trump administration in 2020 authorized TC Energy to increase the line’s capacity by nearly 27% to 760,000 barrels a day. That was significantly more oil than the approximately 600,000 daily barrels Keystone had originally been designed for. The pipeline still had permission to operate at 80% of its SMYS.

Meanwhile, in the same year, the Canada Energy Regulator issued its own industry-wide advisory warning on girth welds.

The record of failures became a focal point for environmental activists opposed to yet another expansion of the line, the high profile Keystone XL project, which President Biden ultimately blocked in 2021 after more than a decade of protests. But the original Keystone continued running, and TC Energy continued to steadily increase the amount of oil that moved through it.

At the time of the December spill, the line was moving 650,000 barrels a day, according to data from Wood Mackenzie. The leak was rapid, according to PHMSA records, gushing more than 12,000 barrels by the time the line was shut — six minutes after alarms went off. Although personnel arriving on site couldn’t see the expanding oil slick in the darkness, they could smell the heavy crude in the air, the agency said in a corrective action order.

The preliminary cause identified — a failed girth weld — spurred PHMSA to order pressure cuts on the entire system until further notice. A final root cause analysis made public Tuesday points to construction “lapses” including inadequate welding, and asserted that TC Energy had underestimated the risks of “girth weld cracking” during its capacity expansion project.

Evan Vokes, a former TC Energy engineer who worked on Keystone, attributes the pipeline’s long history of failures to cost-cutting that compromised safety. The pipeline’s price tag ballooned from $1.7 billion at inception to $5.2 billion in 2008, when it was approved by the State Department, due to the increased size and scope of the project and the material and construction contracts.

“Keystone repeatedly ignored good engineering practice to chase low budget,” said Vokes, who said he was fired from TC after filing a complaint about the company’s practices with Canadian regulators in 2012. Among issues he raised: a failure to follow proper welding procedures, something PHMSA warned TC Energy about in 2013. Following his complaint, Canadian regulators launched an audit of TC Energy, and the company committed to take corrective action.

TC Energy declined to comment on Vokes’ departure, saying in an email that the company “does not comment on personnel matters.”

To date, Keystone has spilled about 26,000 barrels of oil, enough to fill almost two Olympic-sized swimming pools. But it has accrued just $306,000 in federal penalties, a tiny fraction of TC Energy’s $42 billion market cap.

That’s in part because Congress limits PHMSA’s enforcement powers and in part because of how the agency interprets those limits. PHMSA, for example, will not impose the maximum penalty allowed by Congress unless a violation resulted in a fatality or major environmental damage. So far, none of Keystone’s accidents have risen to that level, according to PHMSA. In a statement, the agency said enforcement measures such as warning letters and corrective action orders can incur significant costs that “often dwarf the civil maximum penalties” and these “serve as further deterrence against pipeline failures.”

Critics say that’s not enough.

“The books aren’t strong enough,” said Bill Caram, executive director of the Pipeline Safety Trust, a Bellingham, Washington-based watchdog group. “The PHMSA regulations are really written to grant a lot of latitude to the operator to see how they think best to operate their pipeline.”

That could change. The severity of the December spill, combined with the pattern of worsening leaks, gives PHMSA “a lot more leeway” to take meaningful action, said Cynthia Quarterman, who served as administrator of the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration during the Obama administration.

The agency could, for instance, compel TC Energy to conduct a costly inline inspection that measures the thickness of the entire line pipeline. That so many of the leaks have been linked to welding issues raises the possibility of re-evaluating the special permit that allowed the pipeline to operate under high pressure, Quarterman said.

PHMSA, in response to questions, said it is completing a review of its special permit process and will “apply the results” to Keystone’s and other permits.

For now the pipeline continues to operate, moving about 585,000 barrels of oil a day under contract while the investigation into the December spill continues.

“It’s a fairly new pipeline and you do have to ask those questions,” said Quarterman. “Why are there so many failures?”

--With assistance from Gerson Freitas Jr.